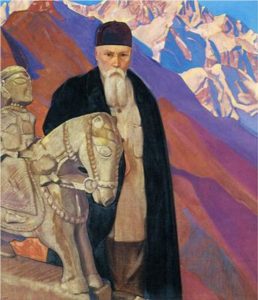

Nicholas Roerich was a painter, a poet, a travel writer, a set/costume designer, and became a follower of various forms of Tibetan spirituality. I knew going into his tiny museum that he and Madame Blavatsky and the infamous Gurdjieff were pioneers of the theosophist movement at the time, and I will not lie, they had some very odd ideas, odd enough that H.P. Lovecraft references Roerich’s art in “The Mountains of Madness”, and I was astonished to learn there are still Roerich Theosophy societies around the world. Who knew?

Roerich’s other main claim to fame is that, after WWI, he was so appalled at the destruction of important art works, historical monuments, and sites that he wrote the Roerich Pact which states that the preservation of important cultural sites and monuments takes precedence over military tactics. The world’s cultural heritage should be preserved. The Roerich Pact has been signed by 21 countries and ratified by 10 of them.

After WWII the UN made a decision to begin the work to regulate armed combat in the presence of important heritage sites. The Roerich Pact was adopted as the model; the work is ongoing.

The Roerich Museum is free (if you ever want to go) and paintings are hung over three floors of a lovely townhouse on W. 107th street – literally a block from my old apartment at 220 W 107th street. I walked by this place a million times without noticing it. I am astonished, but perhaps we don’t see what we need until we need it. Roerich would certainly agree.

The Roerich Museum is free (if you ever want to go) and paintings are hung over three floors of a lovely townhouse on W. 107th street – literally a block from my old apartment at 220 W 107th street. I walked by this place a million times without noticing it. I am astonished, but perhaps we don’t see what we need until we need it. Roerich would certainly agree.

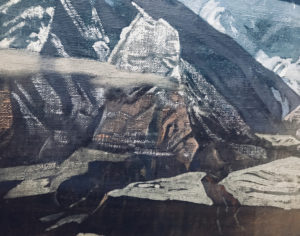

Almost all the paintings are under glass due to their surface delicacy. Roerich painted primarily in tempera. I thought about why this might be, and the answer became obvious. The easy portability of pigments which can then be added to local binders (egg, honey, water, casein) makes using them a smart choice for an artist who plans to paint while traveling.

Tempera paints dry fast. The colors are brilliant. Linen, cardboard, and wood panels are all good substrates, and also some one of these will be available locally, which saves a lot of packing. At a time when acrylics hadn’t been invented, tempera is the smart choice. Oils are too slow drying, and watercolors don’t give the same kind of brilliance. This is close to the same thing I’m choosing to do, except that I’m using acrylic paint and medium as a binder, and I’m choosing to varnish my work to protect that delicate surface.

Examining the surface of his paintings was a treat. I believe he worked with a combination of dry and wet brushes, and possibly some palette knife work. This made me happy because again, I am choosing similar techniques. Because Roerich painted in less than perfect conditions with less than perfectly controlled materials, the surfaces are becoming chalky, and some paintings look like the thicker surfaces are flaking off. But the quality of color has held up well, and I was very glad to see that.

In particular, it was his blues I wanted to examine. Are those colors as fugitive and hard to photograph as mine? They are, and they are magnificent. The use of pure ultramarine with cobalt and white (he also kept a very limited color palette) is striking. I saw again and again areas that appeared to be flat color fields (like the sky) in fact had tonally close shadings in them that you’d never be able to see in a photograph.

What surprised me most were the non-traditional colors. Roerich went to the southwest to paint for a time, and it appears that the colors of rock and sky there influenced his palette in many paintings of the Himalayas. Yellow and cyan skies, purple rocks, and chartreuse greens make appearances. Surprisingly, they make sense. It’s a question of keeping similar tones, and everything works! I really admired his mastery of color.

Thematically, I would stick him in with the Nabis. Mythology and spirituality were important to him. His magnificent landscapes were, in general, backgrounds for this Buddha, or that Kwan-Yin, or some mother earth spirit. My considered opinion was that in most cases, the figures were not necessary for composition, and in fact sometimes were distracting from what I considered the main attraction – the landscape. Roerich would not agree, I am sure. The spirituality and mysticism of his work was everything to him.

I love his daring. He was bold in his color choices, and I would like to emulate that. He was fearless in his life. In his late sixties, he was invited to join an expedition mapping Inner Mongolia and Western Manchuria, and he went, doing many paintings of those areas. He eventually moved to Kullu, India to be near his beloved Himalayas, which is where he died. His ashes were scattered on the slopes of the mountains he loved so much.

The question for me, of course, is was seeing these paintings worth the trip? I think so. Roerich is one of the artists who is obviously an influence on me. I admire his work, and I love how brave he was in his life. It’s given me some things to think about in how I choose to use raw pigment, and ways to think about color that I hadn’t considered before. He worked with pencil sketches taking extensive notes about color and tone on the drawing. I was intrigued by that idea. He did quick oil sketches of some large pieces, and I loved the abstraction of them. Roerich was passionate about his subject in a way I identify with. Even at this distance of time, and with the wall of death between us, it’s still nice to see how someone else chose to cope with their overwhelming passion. We all need role models. He’s a good one for me.